How I Use Obsidian for Taking Notes

- Nohra Murad

- Aug 13

- 5 min read

I started using Obsidian, a Markdown-based note taking app, in January 2025. Six months later, it's become the foundation for my digital life.

I use Obsidian as a lot of things – a daily diary, a personal journal, a keepsake drawer, etc. – but the heart of my Obsidian vault is my personal notes folder, which I call my "zettelkasten."

How It Works

The beauty of Obsidian is that, because it's based on Markdown, I can link notes to each other using hypertext. Notes that otherwise look like they exist in completely separate categories all of a sudden start relating to each other, creating networks of ideas that look less like File Explorer folders and more like a neural network or Wikipedia.

Each note that I write is called a "zettel," or "note" in German, so named after Niklas Luhmann's Zettelkasten system. Each zettel is what productivity geeks frequently call atomic: that is, one idea equals one note, plus any source(s).

Related zettels can connect to each other through hypertext. If a new zettel is a continuation of a thought or concept from a previous zettel, I link the two zettels so that they have a parent-child relationship. If I have a similar idea or concept in my notes, I can link those, too, so they now have a sibling relationship.

By relating my notes to each other organically this way, my notes are able to talk to each other and show patterns between ideas that I otherwise may not have noticed. Obsidian is able not only to link my notes but also to visualize the relationships they have with each other.

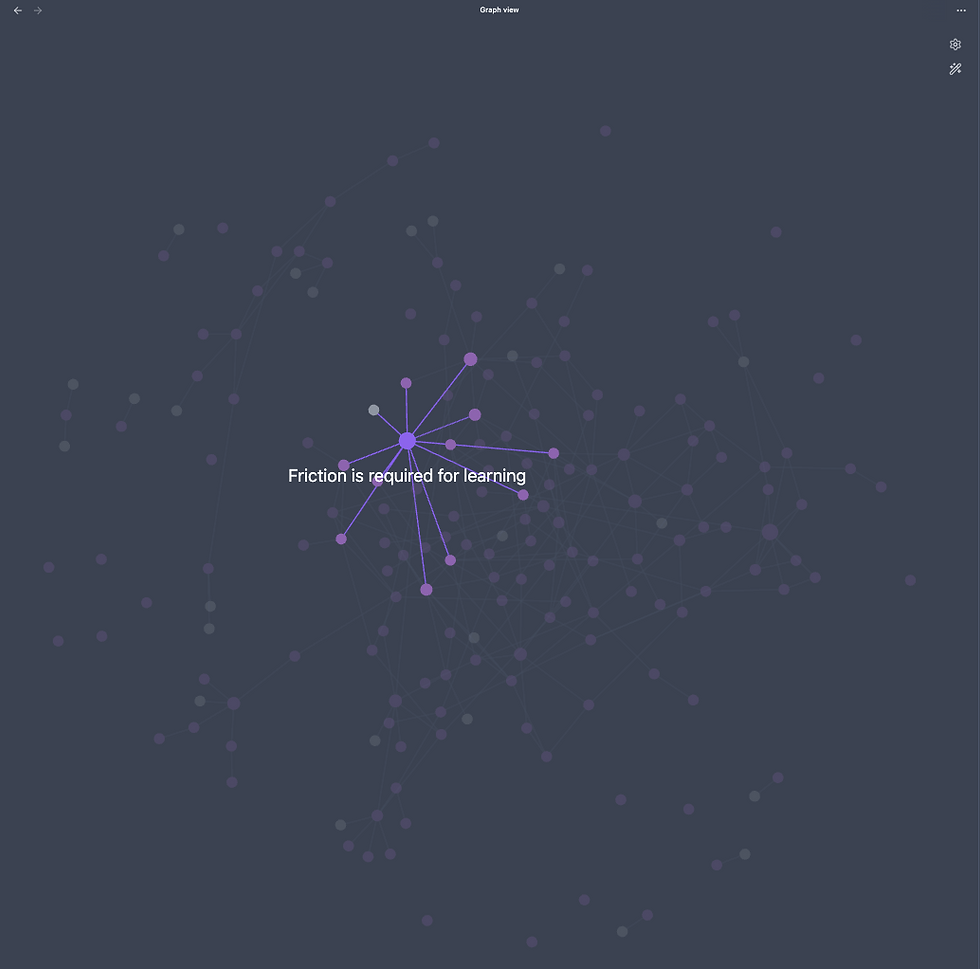

Here's a graphical representation of my Zettelkasten folder, with one node representing one note:

Let's zoom in on one of the biggest nodes, which is my note called "Friction is required for learning." The node is big because many other notes link to it.

The note itself is written in a format I use for all of my notes, which includes the front matter information, links to related notes, and references. The tag indicates if the note has been fully written ("#note/processed") or if I still want to flesh it out further ("#note/toprocess").

Even with this note in the "toprocess" phase, you can see that it still is an important node in my network as it is referenced by many other notes. Thrown in the References section is the source of the thought that inspired it as well as some additional resources for when I get around to building the note out further.

In the meantime, you can see that this note has a lot of links that go to it. Even though the note itself hasn't been fully written, it serves as a node and an entry point for the other ideas flowing around in the network. The idea is also much less likely to go stale: because my notes are so easily visualized and linked in Obsidian, my zettelkasten is able to constantly surface older ideas in a way that reinforces them and makes them feel new again.

I call the infrastructure for my personal notes "zettelkasten-ish." It's not the capital-Z Zettelkasten like that of Niklas Luhmann because, unlike some modern practitioners, I don't adhere to the same nomenclature that Luhmann created working within the constraints of physical drawers and index cards. (It's also because I'm not German and don't capitalize common nouns.)

I've borrowed a few things from Luhmann's Zettelkasten system, such as linking parent-child notes, keeping notes atomic, and prioritizing bottom-up linkage over top-down hierarchy. Otherwise, I've made it into something that works for my own little-z zettelkasten.

What is this all for?

Nothing in particular, quite frankly. I love learning for the sake of learning. I see my zettelkasten as a digital garden that is both a labor of love and an island of sanity in an era of Internet-enabled information overload.

I spend a lot of time working on my zettelkasten. Is it sustainable? I think only time will tell.

For now, though, I enjoy it, and I've found it to be useful for my own development. By tending my digital garden by writing and linking my notes manually, I am also caring for my own mind so that I can hold my thoughts lightly and follow ideas nimbly. Even if all my digital notes are wiped tomorrow, the neural networks I've fostered remain.

This is interesting. Where can I learn more?

I have definitely gone down many zettelkasten and Personal Knowledge Database (PKD) rabbit holes to build my note taking system. I hope to write another post sharing my own Obsidian vault and processes soon.

In the meantime, here are some resources that I found helpful when getting started with Obsidian.

Books

How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens. Ahrens provides a short yet elegant framework for how note taking structures thinking and how a zettelkasten can help.

Digital Zettelkasten by David Kadavy. A short read that gives practical tips for taking digital notes using a zettelkasten structure. I found it well worth the $7.50 I paid for it when it was on sale and would recommend it if you have started a Zettelkasten and want to go deeper.

Resources

Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method (article) on Zettelkasten.de. This post provides the most comprehensive overview of Niklas Luhmann's original Zettelkasten system.

My simple note-taking setup (video, 16:32) by Artem Kirsanov. A great overview of why and how to implement zettelkasten in Obsidian and a beautiful explanation for how it can link your thinking.

FromSergio (YouTube channel) makes great videos about Obsidian features and plugins, particularly this one (video, 10:18) that shows his own workflow.

Ideaverse for Obsidian (sample Obsidian vault) by Nick Milo, the author of Linking Your Thinking. I'll be honest: I have not researched any of Nick Milo's various streams of content (I'm skeptical of anyone whose primary output is a newsletter, a podcast, and online courses – I hope to be proven wrong someday), but I wholeheartedly recommend his sample Obsidian vault. I've gotten some new ideas from exploring it.

This distilled version of Tiago Forte's CODE framework (article) from Workflowy. I read Tiago Forte's book, Building a Second Brain, after hearing it hyped up by productivity influencers, and found a few valuable nuggets in it, but Forte's tips would have been communicated just as well in a blog post. Fortunately, Workflowy summarizes those nuggets in this blog post here, particularly the CODE framework (Collect, Organize, Distill, Express) framework, which I found the most useful takeaway from the book.

Bob Doto (website) and Andy Matuschak (website) have really cool public zettelkasten blogs. Andy even livestreamed a note taking session (video, 1:39:44) to show his thinking and writing process in real time.